Backpacking Skills >> Map & Compass >> Land navigation skills

Backpacking Skills >> Map & Compass >> Land navigation skills

Knowledge of land navigation skills is important for travelers in the backcountry. Being able to find your way in the outdoors is often very useful to prevent oneself from becoming lost in unfamiliar areas. When hiking or backpacking the skills used in land navigation are essential when heading off of marked trails and into the backcountry. For the most successful outdoor experiences all backwoods navigators should know how to properly use land navigation techniques. Also all backcountry travelers should practice Leave No Trace and low-impact hiking techniques.

The earth's magnetic field varies depending on the location as well as changing over time. In the United States the variation between true north and magnetic north can be more than 20 degrees. This difference between the two norths is called declination. The only place where magnetic north is the same as true north is along the agonic line. Declination is 0 degrees alongside the agonic line. Other lines called isogonic lines denote the value of the variations of declination east or west of the agonic line. In 1999 the agonic line ran from the western edge of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to the south western tip of Florida. When using a compass west of the agonic line, the needle points in a direction that is east of true north. This is called easterly declination. When using a compass east of the agonic line, the needle points in a direction that is west of true north. This is called westerly declination.

The earth's magnetic field varies depending on the location as well as changing over time. In the United States the variation between true north and magnetic north can be more than 20 degrees. This difference between the two norths is called declination. The only place where magnetic north is the same as true north is along the agonic line. Declination is 0 degrees alongside the agonic line. Other lines called isogonic lines denote the value of the variations of declination east or west of the agonic line. In 1999 the agonic line ran from the western edge of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to the south western tip of Florida. When using a compass west of the agonic line, the needle points in a direction that is east of true north. This is called easterly declination. When using a compass east of the agonic line, the needle points in a direction that is west of true north. This is called westerly declination.

If you were in an area with a 10 degree west declination it would be very desirable to adjust for declination. To orient a map and compass to true north declination needs to be compensated for. To orient to true north first set the direction of travel arrow on one of the north/south grid lines of your map. Then move the map and compass together and orient to north. Map and compass are now oriented to magnetic north at 0 or 360 degrees. To orient map and compass to true north you need to add a westerly declination (west is best) or subtract an easterly declination (east is least).

With a 10 degree west declination, to get true north you will add 10 degrees. Set the compass at 10 degrees, keep the direction of travel arrow on the grid, and then orient for north again. Map and compass are now facing the direction of true north. When plotting a course on your map that you will follow on the ground with your compass, you will need to convert the map bearing to a compass bearing. If your map is oriented to magnetic north, or if you got your bearing from a protractor, then you need to adjust for declination. The west is best, east is least rule applies here. A 10 degree west declination will change a 60 degree map bearing into a 70 degree compass bearing. You will use the compass bearing to get you headed in the right direction from point A to point B.

If your map is oriented to true north, then when you use your compass to take a bearing from your map, it would already be adjusted for. It would read 70 degrees which is the direction that you want to travel on the ground. A compass oriented to true north in an area with a 10 degree west declination would have a due east bearing of 100 degrees.

If you are converting a magnetic bearing to a map bearing then the west is best, east is least rule does not apply if your map is oriented to true north. If your map is oriented to magnetic north then a map bearing is the same as a compass bearing. To follow the bearing on the ground it only needs to be properly adjusted for declination. If you're in an area with a 10 degree west declination and your map is oriented to true north, a compass bearing of 10 degrees is 0 degrees on the map. You will subtract a westerly declination. It is the opposite of converting a map bearing to a compass bearing. A 280 degree magnetic bearing will be 270 degrees (due west) on a map oriented to true north with a 10 degree west declination. A 70 degree compass bearing is a 60 degree bearing on the map.

There is a simple way to to illustrate why you need to subtract the 10 degree west declination to get the right map bearing. Orient your map and compass to true north for a 10 degree west declination. Your compass should be set to 10 degrees, the direction of travel arrow should be on the north/south grid line, and the needle should be oriented to north. Now set the compass to 70 degrees and count how many degrees there are between 10 degrees and 70 degrees. It is fairly easy to see that there are 60 degrees. This is why you need to subtract a westerly declination or add an easterly declination when converting a magnetic bearing to a map bearing.

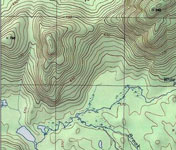

All backcountry navigators should know how to use and interpret topographical maps. Being able to interpret topographical maps will help you in choosing the best route with the least resistance and will also help you to avoid natural barriers like swamps or terrain that is too steep.

All backcountry navigators should know how to use and interpret topographical maps. Being able to interpret topographical maps will help you in choosing the best route with the least resistance and will also help you to avoid natural barriers like swamps or terrain that is too steep.Topographical maps are a pictorial representation of what an area looks like on the ground. The features of the land are represented on the maps by symbols, colors, and lines. They show us distance, direction, and details like landmarks, land boundaries, latitude and longitude lines, and they also show us changes in the level of the land. The changes in the level of the land are indicated by contour lines.

You should always check the date on your map before you adjust your bearings for declination. If your map is old enough you may need to compensate for more declination than the map says. Mooers (1972), says there is an 'annual westward change of 7 minutes' of the earth's magnetic field. The agonic and isogonic lines are slowly moving westward. For example, a 22 year old map of an area in Michigan that reads a declination of 3 degrees west, would now have a declination of 5 degrees and 34 minutes west. The formula for this example is: 22 yrs. x 7 minutes = 154 minutes. 154 minutes/ 60 minutes per degree = 2.56 degrees. 2 degrees + (.56 deg. x 60 min/deg. =33.6 minutes). The new value is 2 degrees and 34 minutes + 3 degrees which = 5 degrees and 34 minutes west.

If the declination that you are working with is a westerly declination then the new value will be a higher one (add the change), if it is an easterly declination the new value will be lower (subtract the change), or if your declination was 1 degree east you may now have a westerly declination. So depending on how old your map is and your location, declination can really be an important factor when using your compass.

Topographical maps come in different scales that show different amounts of detail. The map scales that are most commonly used are 1:62,500 maps (15 minute maps). The distance scale on 1:62,500 maps is 1 inch on the map = 1 mile on land. 1:24,000 maps (7.5 minute maps) are often used and show even more detail. Their scale is 1 inch = 2,000 feet.

Backcountry travelers should be aware of the error factor in map distance. Maps basically measure the distance between 2 points 'as the crow flies'. This differs from the actual distance on the ground unless the land is totally flat. An extreme example of this is the case of a mountain peak. The measured map distance is 1 mile to the top. But with the 60 degree slope of the mountain, the ascent route is twice as long as the portrayed map distance according to Mooers (1972). It is actually 1 mile longer than the distance read off the map. So be aware that the distance measured by maps don't take into account a longer ground distance. Generally if you calculate a hike of six miles, you should figure in map distance error and obstacles, and, as Brown (1980) states, 'be prepared to actually cover about 8 miles'.

A cross-country navigator needs to know how to pace distances. Pacing distances is important when you need to travel a specified distance cross-country to reach your destination. We measure distances so that we know where we are, where we've been, and how much farther we have to go before we reach our target.

A cross-country navigator needs to know how to pace distances. Pacing distances is important when you need to travel a specified distance cross-country to reach your destination. We measure distances so that we know where we are, where we've been, and how much farther we have to go before we reach our target.Paces vary between individuals and with different types of terrain that is traveled. Pacing uses a natural stride for traveling that is equal to 2 steps. To determine or "calibrate" your pace, you first need to accurately measure out a course that you will travel over several times. You will use the number of paces that it took you to travel the course to figure out how many feet your pace is. A course 200 feet in length is a good distance to pace.

Start with your right foot and count every time your left foot hits the ground as 1 pace. To figure out how many feet are in your pace, divide the length of your course by how many paces it took you to travel it. For example: 200 feet/40 paces = a 5 foot pace.

You can use your pace to keep track of your distance while navigating in the woods. A person with a 5 foot pace will have 528 paces in 1/2 mile. Be aware that your pace will vary with the terrain. You will have the least amount of paces on flat ground. Your paces will be longer going downhill and shorter going uphill. It is desirable that you measure your pace for different kinds of terrain. You will probably use your pacing skills mostly when backpacking in areas that have regulations requiring you to choose a backcountry campsite a certain distance (200 - 300 feet) away from trails, water, or historical sites, etc.

When you know your pace, you can take a bearing from your map, set your compass, and head toward your destination. One thing you'll want to do is turn your map (orient it) so that it coincides with the ground in front of you, so that your destination is in the right place. Your map may be sideways or upside down but you still will be able to orient it with your compass. Once you have your map, compass, and pacing skills you could test your skills by setting up a compass course.

One way to keep as much of a straight line as possible, is to sight on some distant landmark in line with your desired bearing, and then to travel to it. This will keep you from drifting off course. Studies have shown that 'man has a natural tendency to circle' (Rutstrum, 1967). The most accurate type of compass is one that has a mirror sight. This kind of compass allows you to sight on distant objects and look at your compass at the same time. When sighting be sure to sight with your dominant eye to avoid errors.

Navigators should be aware that the compass can also be affected by the presence of steel, iron, electrical lines, and mineral deposits. The needle will tend toward magnetic north but will register the direction of the strongest magnetic influence wherever it may be. So when using a compass, be aware of things that could give you a faulty reading and lead you off course, and try to stay away from them.

Another method you can use to get to where you are going is called over sighting or following what Rutstrum (1967) calls an 'intentional deviation course'. The compass is not 100% accurate. There is a slight margin of error. Let's say that you were headed due north to get to a small waterfall that you want to see. The river is 1 mile ahead of you and is flowing east to west. So the whole river is north of you. From where you are located your map bearing tells you that the waterfall is at 0 degrees; due north of you. You travel due north for 1 mile, but while you are traveling you somehow stray off course slightly. So you reach the river but you have not reached the falls, and you can't hear them either. Now you have to decide which way to follow the river to get to your objective.

To avoid having to guess which direction to take to get to your destination, you can intentionally over sight your target. You can take a bearing, let's say, 20 degrees east of of your destination. Then when you reach the river you will know that you have to follow it west to reach the waterfall. With following an intentional deviation course you can be sure of which direction to travel when reaching the river.

An understanding of land navigation skills is very important for outdoor enthusiasts who wish to explore and travel through the backcountry. We need them to determine direction, interpret maps of the area where our adventure will take place, plot routes on a map and correctly follow them on the ground, and we need them to determine the distance of our journey. As responsible backcountry travelers we need to be sure to practice Leave No Trace hiking techniques Knowing all these backcountry navigation skills will make excursions into the backcountry safer and more satisfying experiences.

Like it? Share & bookmark this page!